You are here :

Home Biodiversity Hotspots in India

|

Last Updated:: 07/10/2021

Biodiversity Hotspots in India

GLOBAL BIODIVERSITY HOTSPOTS

WITH SPECIAL EMPHASIS ON INDIAN HOTSPOTS

INTRODUCTION

Biodiversity is a contraction of the term “biological diversity” that refers to variety among and between living organisms. The term biological diversity was used first by Arthur Harris (1916), an American botanist in his article "The Variable Desert" published in a science magazine called, The Scientific Monthly as part of a statement: “The bare statement that the region contains a flora rich in genera and species and of diverse geographic origin or affinity is entirely inadequate as a description of its real biological diversity”. The term, “biodiversity” was first coined by Walter G. Rosen in 1985. This widely used term biodiversity does not have a universally unified definition as it is often redefined according to the context and purpose of the each author (Swingland, 2001). However, biodiversity is usually defined by the biologists as the “totality of genes, species and ecosystem of a region”. Generally, biodiversity is divided into three fundamental categories namely genetic diversity, species diversity, and ecosystem diversity.

Biodiversity is very often regarded as a synonym of species diversity, and measured by the number of species in a particular area, species richness (Swingland, 2001). The distribution of biodiversity is neither random nor uniform on earth (Noss & al., 2015). The distribution of species is highly concentrated in specific geographical regions of the world. Over two-thirds of world’s biodiversity occur in tropical areas, especially in tropical forests (Raven, 1988; Pimm & Raven, 2000). The tropical zones with high level of species diversity have been identified as “Biodiversity Hotspots”.

History of Biodiversity Hotspot

The term ‘biodiversity hotspot’ was coined by Norman Myers (1988). He recognized 10 tropical forests as “hotspots” on the basis of extraordinary level of plant endemism and high level of habitat loss, without any quantitative criteria for the designation of “hotspot” status. Two years later, he added eight more hotspots, and the number of hotspots in the world increased to 18 (Myers 1990).

Subsequently, the Conservation International in association with Myers made the first systematic update of the hotspots, and introduced the following two strict quantitative criteria, for a region to qualify as a hotspot:

(i) It must contain at least 1,500 species of vascular plants (> 0.5% of the world’s total) as endemics;

(ii) It has to have lost ≥ 70% of its original native habitat.

The first systematic update of the hotspots, which involved an extensive global review, introduced seven new hotspots on the basis of the newly defined criteria and authentic new data, thus the number of hotspots has been increased to 25 (Mittermeier & al., 1999; Myers & al., 2000). The second systematic update revisited the hotspot regions and redefined several hotspots based on the distribution of species, threats, and changes in the threat status of these regions, which resulted in addition of nine more hotspots thus the number of hotspots expanded to 34 (Mittermeier &t al., 2004). The “Forests of East Australia” harbouring at least 2,144 endemic vascular plant species in an area with just 23% of its original vegetative cover remaining was identified as the 35th biodiversity hotspot (Williams & al., 2011; Mittermeier & al., 2011). In February 2016, the “North American Coastal Plain” meeting the criteria of hotspot, was recognized as the 36th global biodiversity hotspot.

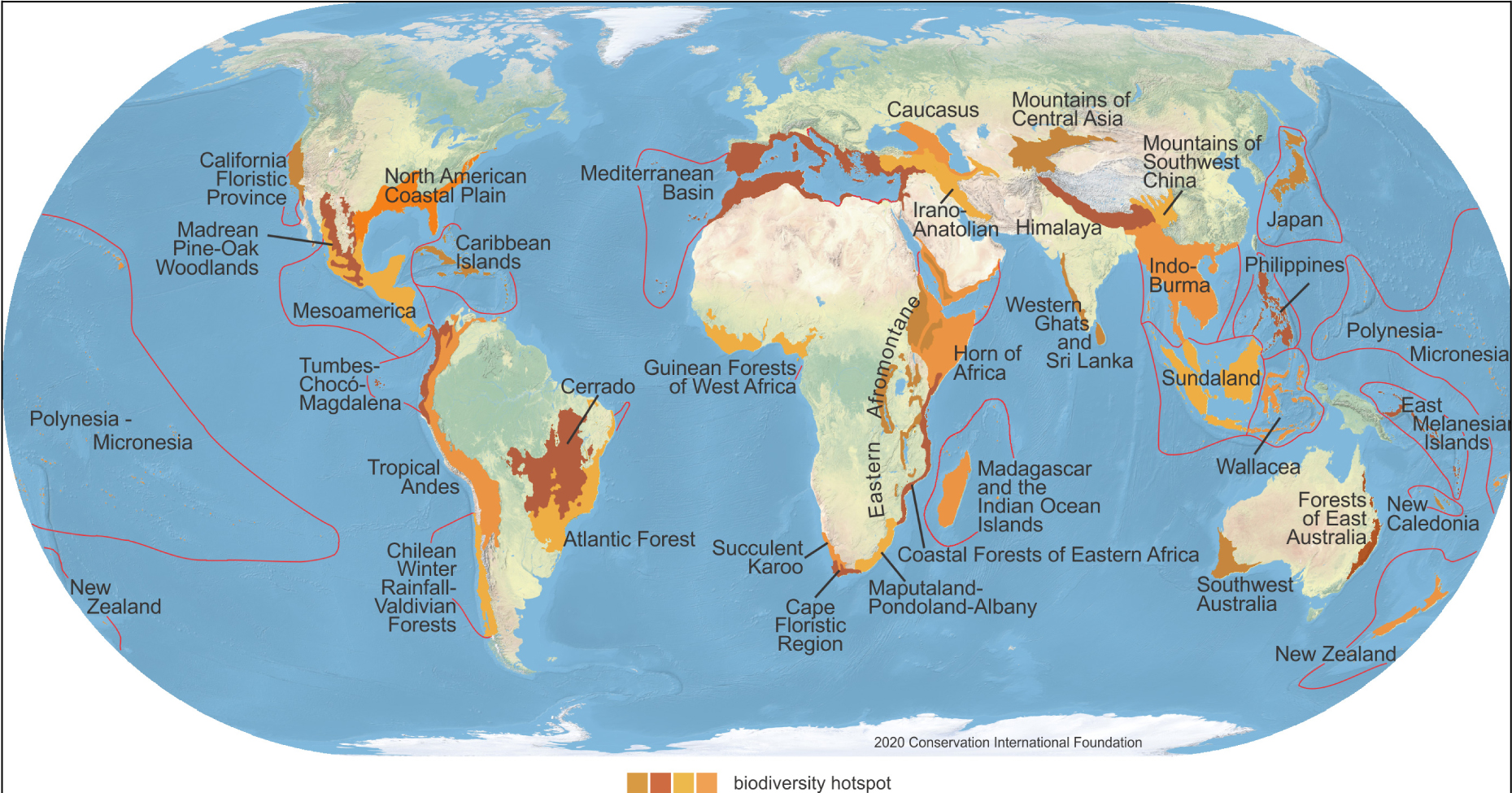

Therefore, according to Conservation International (https://www.conservation.org), at present, there are 36 biodiversity rich areas in the world that have been qualified as hotspots, which represent just 2.5% of earth’s land surface, but support over 50% of the world’s endemic plant species, and nearly 43% of bird, mammal, reptile and amphibian species as endemics. Table 1 provides the regions that have been recognized as the biodiversity hotspots of the world, the same is also depicted in Fig. 1.

Table 1. Biodiversity Hotspots in the World

Sl. No.

|

Name of the Hotspot

|

Location

|

1.

|

Tropical Andes

|

South America

|

2.

|

Tumbes-Choco-Magdalena

|

South America

|

3.

|

Madrean Pine–Oak Woodlands

|

North and Central America

|

4.

|

Cerrado

|

South America

|

5.

|

Chilean Winter Rainfall and Valdivian Forests

|

South America

|

6.

|

Atlantic Forest

|

South America

|

7.

|

Mesoamerica

|

North and Central America

|

8.

|

Caribbean Islands

|

North and Central America

|

9.

|

California Floristic Province

|

North and Central America

|

10.

|

Guinean Forests of West Africa

|

Africa

|

11.

|

Cape Floristic Region

|

Africa

|

12.

|

Succulent Karoo

|

Africa

|

13.

|

Maputaland–Pondoland–Albany

|

Africa

|

14.

|

Coastal Forests of Eastern Africa

|

Africa

|

15.

|

Eastern Afromontane

|

Africa

|

16.

|

Horn of Africa

|

Africa

|

17.

|

Madagascar and the Indian Ocean Islands

|

Africa

|

18

|

Mediterranean Basin

|

Europe and Central Asia

|

19.

|

Caucasus

|

Europe and Central Asia

|

20.

|

Irano-Anatolian

|

Europe and Central Asia

|

21.

|

Mountains of Central Asia

|

Europe and Central Asia

|

22.

|

Western Ghats and Sri Lanka

|

South Asia

|

23.

|

Himalaya

|

South Asia

|

24.

|

Mountains of Southwest China

|

East Asia

|

25.

|

Indo-Burma

|

South Asia

|

26.

|

Sundaland

|

Southeast Asia and Asia-Pacific

|

27.

|

Wallacea

|

Southeast Asia and Asia-Pacific

|

28.

|

Philippines

|

Southeast Asia and Asia-Pacific

|

29.

|

Japan

|

East Asia

|

30.

|

Southwest Australia

|

Southeast Asia and Asia-Pacific

|

31.

|

East Melanesian Islands

|

Southeast Asia and Asia-Pacific

|

32.

|

New Zealand

|

Southeast Asia and Asia-Pacific

|

33.

|

New Caledonia

|

Southeast Asia and Asia-Pacific

|

34.

|

Polynesia–Micronesia

|

Southeast Asia and Asia-Pacific

|

35.

|

Forests of East Australia

|

Southeast Asia and Asia-Pacific

|

36.

|

North American Coastal Plain

|

North and Central America

|

Fig 1. The 36 currently recognized biodiversity hotspots in the world (https://www.cepf.net)

Biodiversity Hotspots in India